In the new memoir, Home Baked: My Mom, Marijuana, and the Stoning of San Francisco, writer Alia Volz tells the story of her mother’s 1970s cannabis edibles business, which sold around 10,000 illegal pot brownies every month throughout San Francisco.

“I had been my mom’s accomplice since I was in the stroller,” Volz writes. “Before I could spell my own name, I understood that I came from an outlaw family.”

In 1976, before Alia was born, her mother, Meridy Volz, teamed up with Shari Mueller, who sold baked goods out of a picnic basket on Fisherman’s Wharf, a tourist hot spot in San Francisco. They sold regular brownies for a quarter and “magic” brownies with pot for a dollar apiece, until Mueller left the city for a commune in Scotland. As her brownies business boomed, Meridy soon became known as “the Brownie Lady,” selling her weed treats out of Alia’s stroller to disco stars, the long-running musical revue Beach Blanket Babylon and at the campaign headquarters of San Francisco politician Harvey Milk.

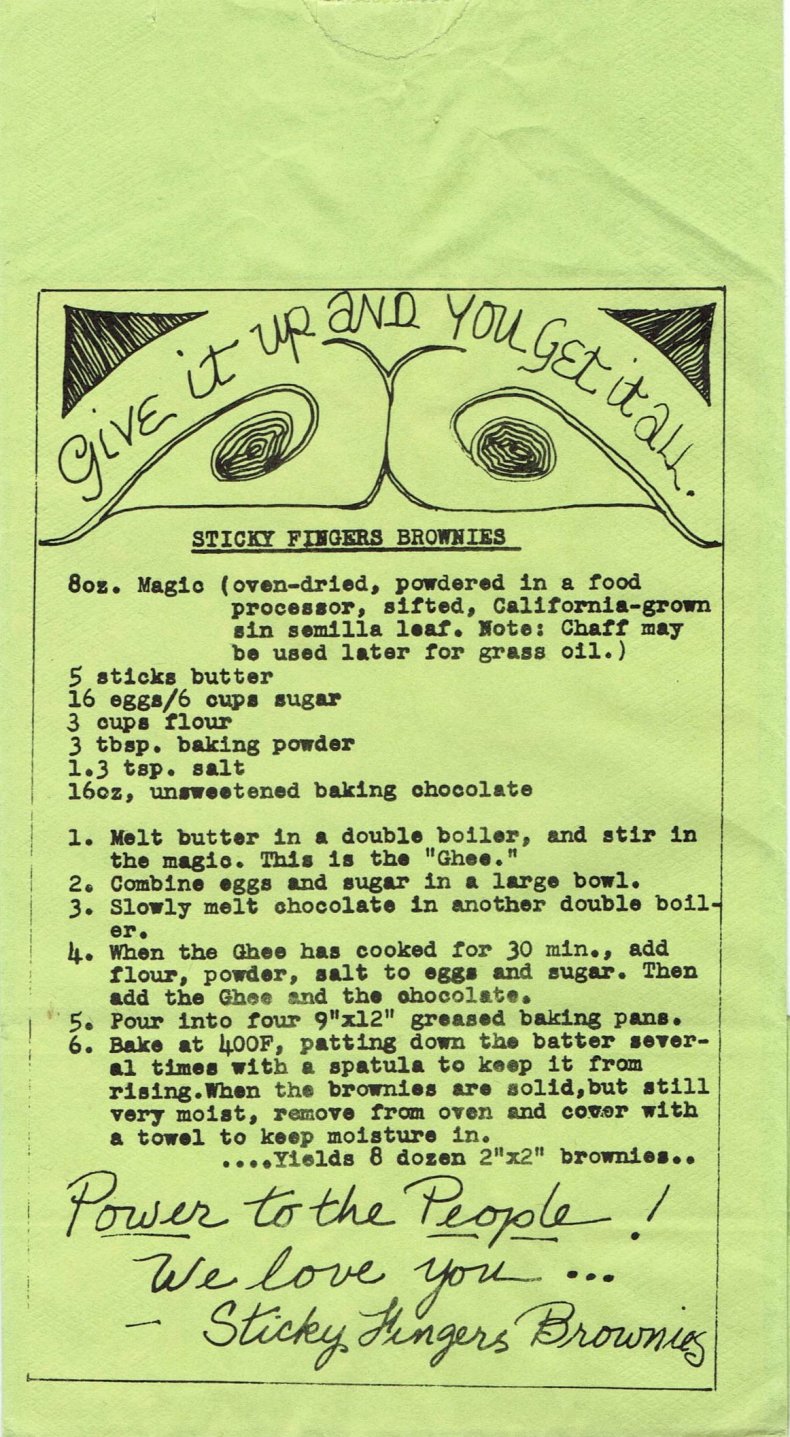

Selling primarily to familiar Wharf buskers and a growing list of trusted clients, Meridy would eventually distribute more than 10,000 brownies monthly, delivering each brownie in hand-illustrated lunch sacks and branded as “Sticky Fingers Brownies” (after the Rolling Stones album of the same name). Expanding business meant more weed and more risk—eventually Sticky Fingers was using whole garbage bags full of cannabis “shake” (small pieces of cannabis flower and dust) in the process.

“This was the Wild West, when growing a single marijuana plant was a felony,” Volz told Newsweek. “Sticky Fingers Brownies sourced their weed from small, independent farmers in Humboldt and Mendocino counties. This is before hybridization gave us strains that smell like bubblegum and blueberries. Back then, the marijuana had terroir, as wine does. It smelled like redwoods, river moss and road dust. As the brownie business exploded in San Francisco, the need for shake drove them deeper into the woods, down endless dirt roads, and way off the grid.”

Much of the baking was done by Meridy’s best friend, Barb, who cooked in a windowless warehouse in the city’s Mission District. It was Barb who accidentally came up with their Fantasy Fudge—a new recipe with unexpected potency that brought ballooning sales and became a Sticky Fingers signature.

“One night when Barb was up late baking, she forgot to add flour to a round of batter,” Volz told Shelf Awareness in a Friday interview, beginning one of her favorite anecdotes from Home Baked.

“Realizing her silly mistake, she pulled the undercooked brownies out of the oven and started absently licking the batter from her fingers,” Volz said. “Next thing she knew, she was flying. Barb had accidentally discovered a key element in weed cooking. Heat makes the plant release THC, increasing potency. But too much heat causes the THC to dissipate. Barb had found the sweet spot. From then on, her brownies were always undercooked, left molten and jiggly in the center. This made for an infamously intense high.”

Volz described to Newsweek how the weed cooking of that era lacked the refinement of modern methods. There was no way to measure the precise content of THC, cannabidiol or other cannabinoids in a Sticky Fingers brownie. Instead, they relied on anecdotes from customers.

“Back then, you simply ground the marijuana to a flour-like consistency and dumped it into the batter,” Volz said. “Nevertheless, the Sticky Fingers recipe was highly coveted in its day. People tried to buy it, but my parents wouldn’t sell. When they closed the business temporarily in 1979, they decided to give the secret recipe to their customers by printing it on the package, along with the message, ‘Give it up and you get it all. Power to the people!'”

Initially a recreational party treat, Sticky Fingers Brownies took on a new purpose as the AIDS virus began spreading through the LGBT-friendly neighborhood known as the Castro in 1982. The disease was known as “gay cancer” or gay-related immune deficiency early in the outbreak, and sufferers were neglected by federal authorities and mocked by the media throughout the 1980s, as thousands died from a disease with a 1-in-3 mortality rate.

“Have you been checked?” Ronald Reagan’s press secretary Larry Speakes joked with a reporter in 1984, after admitting to a giggling press pool he hadn’t heard Reagan address or express any concern related to the outbreak. By that point, more than 3,600 people in America had already died of the disease.

As AIDS spread among Meridy’s clientele, Sticky Fingers Brownies became an incidental pioneer in the medical use of cannabis for palliative care. Thanks to her large community of buyers—a widening circle of trusted friends—her business became a ready-made “underground network” capable of getting the illegal medication to sufferers in need of relief.

“At its heart, Home Baked is about community—how an underground network that came together during the party days reinvented itself to provide care and support during the HIV/AIDS epidemic when faced with government inaction,” Volz told Newsweek. “Dealers became healers. Now that we’re faced with a new pandemic, I think it’s inspiring to remember how this community evolved when the brownie batter hit the fan.”

While a memoir, Home Baked is also an intensively researched book on San Francisco and the burgeoning cannabis culture surrounding Sticky Fingers Brownies, based on archival research and hundreds of hours of interviews with LGBT activists, cannabis advocates and, of course, Volz’s parents.

Home Baked also provides a timely contrast with both modern San Francisco and the blossoming cannabis industry, which can now offer safe and legal access to the drug, although significant reforms to the war on drugs have not materialized.

“The people who bore the brunt of the drug war [illegal farmers and communities of color] are being left out in the cold,” Volz said. She noted that Home Baked reflects “the broader transformation of San Francisco, from a haven for artists, outcasts and dreams to an increasingly drab playground for the nouveau riche of the tech world.”

Home Baked: My Mom, Marijuana, and the Stoning of San Francisco by Alia Volz is out now in hardcover from Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. A movie may be on the way as well: Home Baked has been optioned by J.J. Abrams’ Bad Robot Productions.

Recent Comments